Out on an Island

After very different military careers, two men find themselves in the same classroom facing many of the same struggles.

Former US Army soldiers, Joseph Marcinko and Dustin Bader, sat in a classroom tucked away in Ohio University’s Baker University Center in Athens, Ohio. They were in their Military Student Transition Seminar class. The two men, like most first year students at OU, are enrolled in a class aimed at helping new students. This class is not about the transition from high school to college — it is designed for both current and former military service members.

Like the training both men received at Fort Benning in Georgia during their time in the Army, they were being prepared for their next challenge. Instead of being prepared for combat and conflict, Marcinko and Bader are learning how to come home.

Both men have been out of the military for several months but are still adjusting to civilian life. Doctors can treat medical conditions and chronic symptoms born from the rugged lifestyle of serving at home and abroad. But many veterans find they need mental health services to help them rejoin civilian life. In southeastern Ohio, where treatment options are limited, Ohio University offers programs and services to veterans pursuing a higher education.

Dustin Bader, 26

Joe Marcinko, 37

Marcinko joined the Army in 2002. The United States was reeling from the 9/11 attacks and began military operations in the Middle East. At 19 years old, Marcinko wanted to get out of his Appalachian hometown of Tuppers Plains, Ohio, so he enlisted in the United States Army. His decision to join was rooted in patriotism and tradition, but he also wanted to prove doubters wrong and show that he could thrive in the military.

For the next 17 years, Marcinko was a career military man. He did two tours in Iraq and one in Afghanistan. He also served as sniper school instructor and a recruiter.

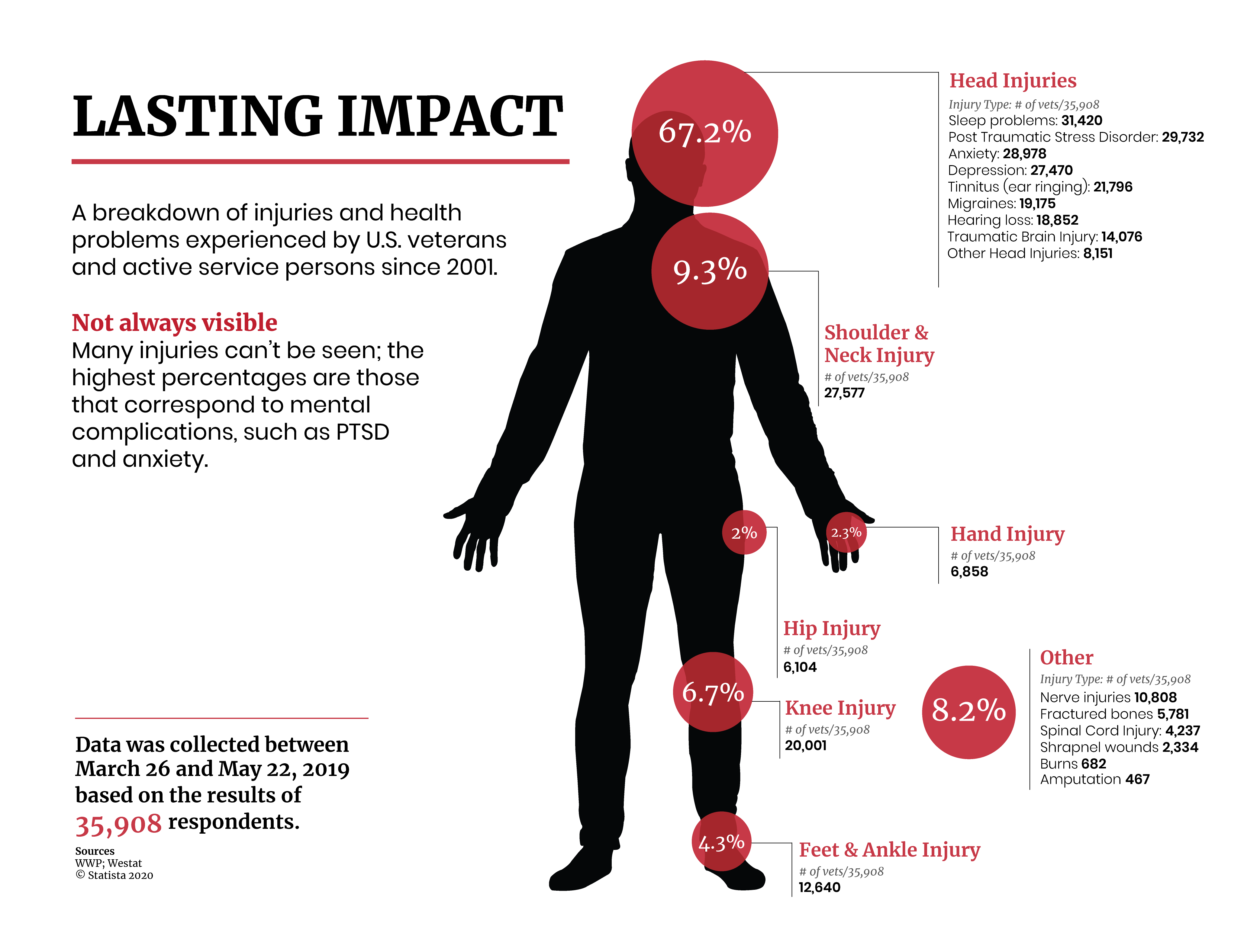

Not all ailments sustained in the military are physical and not all serious injuries happen in active combat zones.

During his deployments he experienced combat. As a result, he sustained numerous physical injuries. He has had three shoulder surgeries and jaw surgery, suffered from a concussion and still has three pieces of shrapnel in his back from a rocket propelled grenade explosion in Afghanistan.

Marincko, not knowing the toll combat had taken on his mental and neurological health, thought his experience in the military was normal. Marcinko didn’t think he experienced anything that bad. However, towards the end of his military career he had a breakdown — Marcinko needed help.

Joseph Marcinko discusses his battle with PTSD and reintegration into civilian life.

Bader grew up in foster care. At 16-years-old he was kicked out of his foster home and moved in with a friend and his family. His friend’s father encouraged him to join the military. Bader knew he wasn’t ready for college, but wanted purpose in his life. He took the advice his friend’s father gave him and joined the Army in 2012. He too was only 19 years old.

As a teenager, Bader was accustomed to relaxed expectations and having few responsibilities. Joining the military was a culture shock. He suddenly found himself facing strict rules and constant competition with his peers and supervisors.

Bader was also faced with the likelihood that he would never see combat. As the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq evolved, fewer soldiers were being deployed to the Middle East. Bader spent most of his military career in Colorado guarding munitions in a classified facility. While he found his work to be important, it was discouraging for him to know that he was almost guaranteed to never go overseas.

During his enlistment, Bader suffered a brain injury. He was throwing hand grenades during a training exercise at the range, but a fellow soldier failed to clear the protective barrier and the grenade exploded in the pit where they were standing. Luckily, they both escaped the shrapnel but the pressure wave from the explosion caused a head injury. Bader received a traumatic brain injury from the incident and he needed three weeks of medical care to recover.

Bader found himself struggling with the culture of the military. After three years of service, Bader made the decision not to re-enlist and rejoined civilian life. The thought of freedom was euphoric for him, but the lack of structure to his life created new obstacles that he struggled to overcome before finding his way to Ohio University.

Dustin Bader tells his story of the challenges of returning to a world he was conditioned to forget.

After Marcinko’s breakdown he reached out for mental health treatment. Marcinko spent a month at an in-patient treatment facility. Following this, he resided in Syracuse while in the process of being transferred to a warrior transition unit. These units work with soldiers who need six or more months of rebabilitvate care, therapy or medical management. During this time, he drove over an hour each week to a military base in upstate New York for counseling. This counseling, done through Veterans Affairs, is what led doctors to discover the extent of the stress and neurological damage Marcinko sustained in combat.

Marcinko has used a variety of medicines and counseling to cope with the things he experienced in Afghanistan and his transition back into civilian life. As his body healed he was able to resume strenuous physical activity, which helped both his mental and physical health. Marcinko ran 12 half-marathons in the year after he retired and works out almost daily in either the gym he built in his garage or between classes at Ohio University’s recreation center.

Marcinko, a former high school athlete, wanted to give back to his community. He took his passion for sports and started volunteering at his alma mater, Eastern High School, as an unofficial equipment manager. High school coaching gave him the sense of team cohesion he missed and something to work towards. He spent the summer cleaning and renovating Eastern’s football locker room. He also helped the school replace old football uniforms. He built strong relationships from this and wanted to continue, so he reached out to his former basketball coach.

Marcinko’s high school basketball coach is the head boy’s basketball coach at Trimble High School. Marcinko reached out in hopes of finding a coaching position so he could learn more about coaching from someone he admired. Marcinko was invited to work as an assistant coach at Trimble. This position exposed him to many of the things he missed about the military, like comradery, teamwork and discipline. He has been in this position since January.

While his civilian experience has improved, Marcinko acknowledges the physical, mental and emotional struggles have not been easy to overcome. But he continues to try. “I can get up every day and push through it, or I can just lay in bed and cry about it,” said Marcinko. He pushes through.

Marcinko observed the junior varsity players he helped coach during a game against Alexander High School.

When Bader left the military, he returned to Cincinnati. During the day, he would sit at a park with nothing to do and nowhere to go, he recalls. At night, he would stay at friend’s homes and sleep on couches.

Bader had lost the purpose he joined the military for. He felt small. He wanted to talk about these feelings, but he struggled with finding someone who would understand. He sought out help from the VA, but at his appointment he was met with a depression diagnosis and a prescription for antidepressants. While medication can help manage mental health conditions, Bader was looking for someone to talk to and work through his struggles with. He needed more than he was offered.

Bader says he started doing drugs. He was using opioids and marijuana. When one of his close friends suffered a fatal overdose, Bader realized he needed to find his purpose.

Dustin Bader relaxes in his living room with his dog.

Marcinko and Bader both found themselves on Ohio University’s campus in January looking for an education to help them achieve their goals.

The traumatic brain injury Marcinko received in combat resulted in him reading slower and needing more time to fully grasp the concepts he is learning. However, similar to how he was able to work through his physical ailments and treat his mental struggles, he continues to push himself academically.

Ohio University has over 800 self identified veterans for the 2018-2019 academic year, according to Terry St. Peter, interim director of the university’s military student service center.

Both men are older than many of their peers. Marcinko finds it frustrating that many of his classmates, and some of his professors, are ignorant to the world beyond what affects them. Bader has found structure at OU, though. He appreciates how relaxed civilian life can be. Due to the age gap between him and many of his classmates, he tends to look for companionship off Ohio University’s campus at the Smiling Skull. This bar, which typically has multiple motorcycles parked out front, is a uniquely gritty small-town establishment. Many customers are locals that have been frequenting the bar for years. Bader spends time there between his afternoon classes chatting with other customers, sometimes new people and sometimes regulars. It has given him the opportunity to meet interesting people and join a small community.

Dustin Bader takes notes during his Military Student Transition Seminar class. The class designed to help veterans' transition to student life and is led by the Veterans and Military Student Services Center at Ohio University.

Bader and Marcinko joined the military for different reasons and had vastly different careers. They both faced adversity as a result of their military service and struggled at times to rejoin civilian life. The road home is long, but there is hope.

Joe Marcinko stands for a portrait by his dress uniform in Tuppers Plains. Marcinko had the uniform framed and put on display after he was honorably discharged.